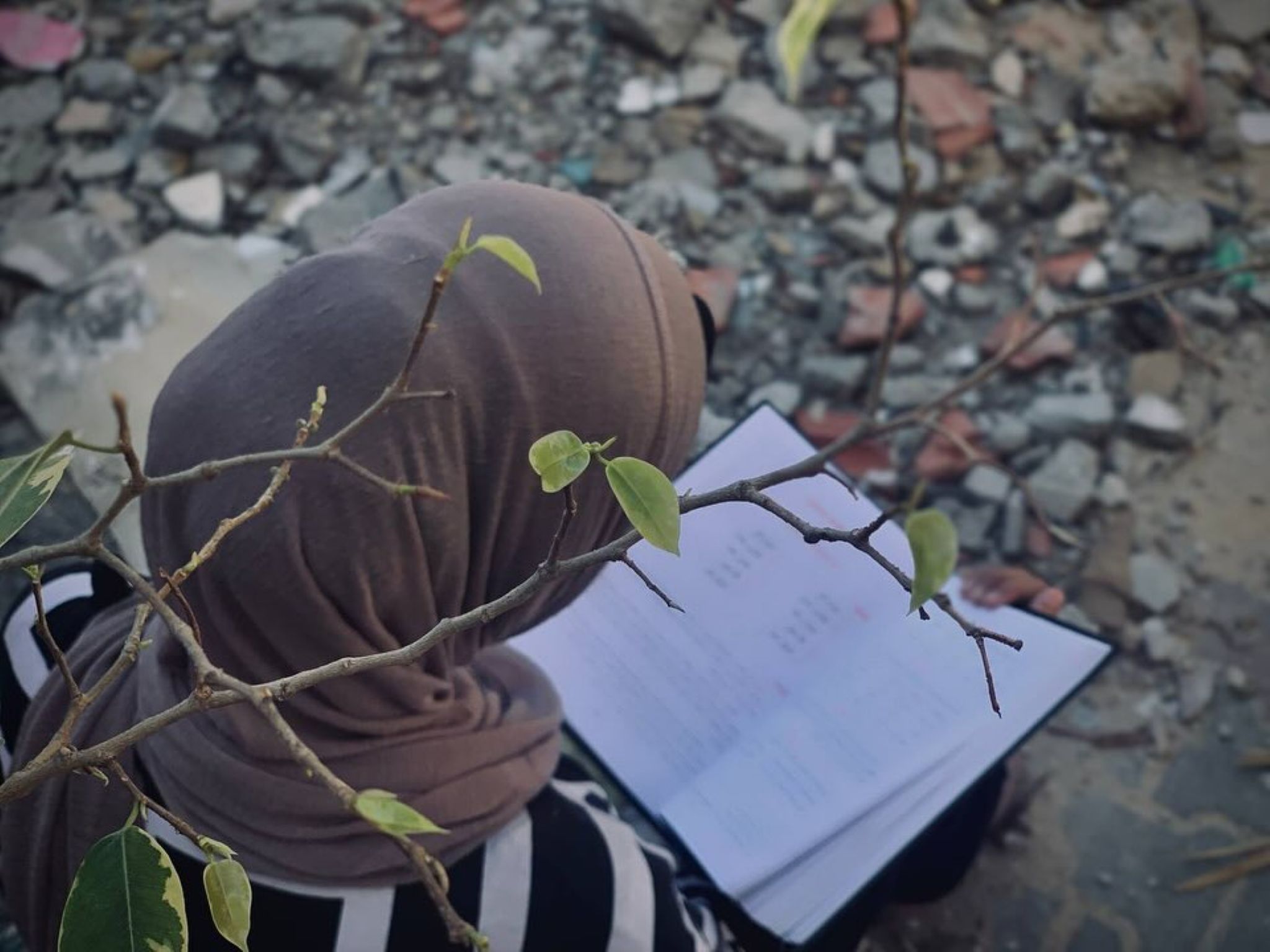

The last math class I took with Mr. Nabil ended on an afternoon in May 2021. That year, the semester was cut short by an Israeli aggression, not the first nor the last in the Gaza Strip. I quickly arranged my books and raced to exit through the school’s small, antique door. I stood outside the building, looking at it, contemplating its dark interior, which used to be a convenience store. A question passed through my mind: Did it ever occur to the convenience store that someday, calculus classes would be taught there? I laughed to myself, a disappointed laugh. When the difficulty of our circumstances is greater than our ability, the scenario that we envision for our lives escapes us.

My teacher exited the building and we began walking together. After I shared my opinion on the war we were living through, I felt that he wanted to tell me something. He seemed to sense that the war had extinguished whatever enthusiasm I once had. That afternoon, we walked beneath a golden sun, past the concrete blocks of a refugee camp that had been established in 1948. The summer sky was clear except for the drones, which never seemed to leave us, not even in times of truce. The teacher asked me:

— So, how are your studies?

— They’re going pretty well, but I feel my concentration has been disrupted by what’s happening.

— Final exams are coming up; what choice do you have but to keep going? You always manage to solve the difficult questions. I can see you’ll be among the top students in the class. Tell me, will you go to medical school?

I took refuge in silence and recalled a story Mr. Nabil once told us about how, as a youth, he’d wanted to study medicine. He was an extremely sharp student, unrivaled in his talent, but his family circumstances prevented him from pursuing it. His parents’ generation was among the Palestinians who were displaced in 1948 and settled in the camps. He is now over sixty and has witnessed all the events of the Strip, from invasions to uprisings to bombing raids. All of these circumstances converged, and he became one of the most important math teachers in central Gaza’s refugee camps and one of the greatest inspirations of my life. His life may not have turned out the way he had dreamed it would, but even the convenience store didn’t know it would become a place to study the limits of integration.

He interrupted my thoughts:

— Have you decided on your major, Dima?

— I haven’t yet, but I don’t feel that I have the freedom of choice. Gaza’s brightest students don’t have many options for majors besides medicine and engineering. But for me, my obsession is physics.

— Physics? The opportunities for that specialization are limited here.

— The opportunities in general, Mr. Nabil, are limited by the siege and the occupation’s regime of strangulation and the fear that hovers around us. Whoever excels in their studies either suffers and eventually leaves or stays here and is assassinated by Israel.

At that moment, I’m sure that the same thought crossed our minds, because we both fell silent. During the aggression that spring, Israel bombed the home of the physics teacher, seriously injuring him and killing his wife and daughter. We did not say the names of our martyrs out loud because we feared that the occupation would hear us, even in the streets. “Physics, physics,” my teacher mumbled.

— Then travel if that’s the case; I studied math in Baghdad.

— Baghdad was different in your day than it is in mine, Mr. Nabil.

— The day it fell was the hardest of my life. In the past, Baghdad was my country…

We continued walking in silence through the camp, which was packed with concrete houses. When Mr. Nabil arrived at the place where he was teaching another group of students, I bid him farewell. “Don’t forget to study hard for the final exam,” he said. I nodded in agreement and looked at him faithfully. He looked at me with pride.

In April 2024, on the anniversary of the fall of Baghdad, Mr. Nabil said that the US invasion was one of the greatest shocks of his life. The city of Mr. Nabil’s past was ravaged by wars, and the city of his present, Gaza, had been stripped of every semblance of life by the occupation. The futures that the people of these cities envisioned have not yet been realized.

I apologize to you, Mr. Nabil, on behalf of fate, because you dreamed of a free place in your past and your present. You dreamed of a place that would endure, that would never be erased by the hands of barbarity, that would respect reason and knowledge, and that, above all, would respect human life.

To Mr. Nabil: The difficulty of our circumstances was greater than our ability. We often choose what best suits the conditions of our country, not the conditions of our dreams. Though I once envisioned myself studying physics, I now study literature and write the story of my people. You became one of the best math teachers in Gaza, not a doctor as you once aspired, and you helped many generations of the country’s youth.

And to the convenience store: I apologize because I know that if you had been the convenience store that you wanted to be, you wouldn’t have been so dark and cramped inside. I wonder if you, like me, find it ironic that we study the limits of integration in a country where everything is limited.

Dima Hattab was born and raised in the Bureij refugee camp in central Gaza, where she continues to live during the ongoing genocide. She studies English literature online at the Islamic University. This piece has been translated from Arabic and appears in the nineteenth issue of The New York War Crimes.