In the early months of the second Trump presidency, it has become difficult to distinguish between attacks on Palestine solidarity within U.S. universities (themselves engines of imperialism) and attacks on higher education writ large. Trump and his billionaire allies seek to limit access to education and other public goods as a means of lowering the general population’s standard of living and consolidating ruling class power over all facets of life. A key reason the American political elite is incentivized to suppress Palestine solidarity activism is that the truth of Zionism’s genocidal assault on Palestinian life in Gaza makes clear to the world’s masses how they too will ultimately be made disposable — their very existence treated as a problem to be solved.

We would be mistaken to conclude that attacks on public goods and civil society are separate from attacks on Palestine solidarity in the West. Rather, as Trump’s early agenda has revealed, full-scale assaults on these sectors of society are often motivated by the simple fact that they contain spaces for resistance against ruling-class power (and Zionism in particular) and resources that can be repurposed for resistance. Attacks on education can be seen from this perspective as they are part of the larger project of eliminating any piece of society that can become a haven of resistance. Zionist assaults on DEI, affirmative action, and “wokeness” are paradigmatic examples: They have become liabilities because they create conditions for resistance and provide a set of ideas that are ultimately incompatible with Zionism’s genocidal racism and project of settler-colonial elimination in Palestine.

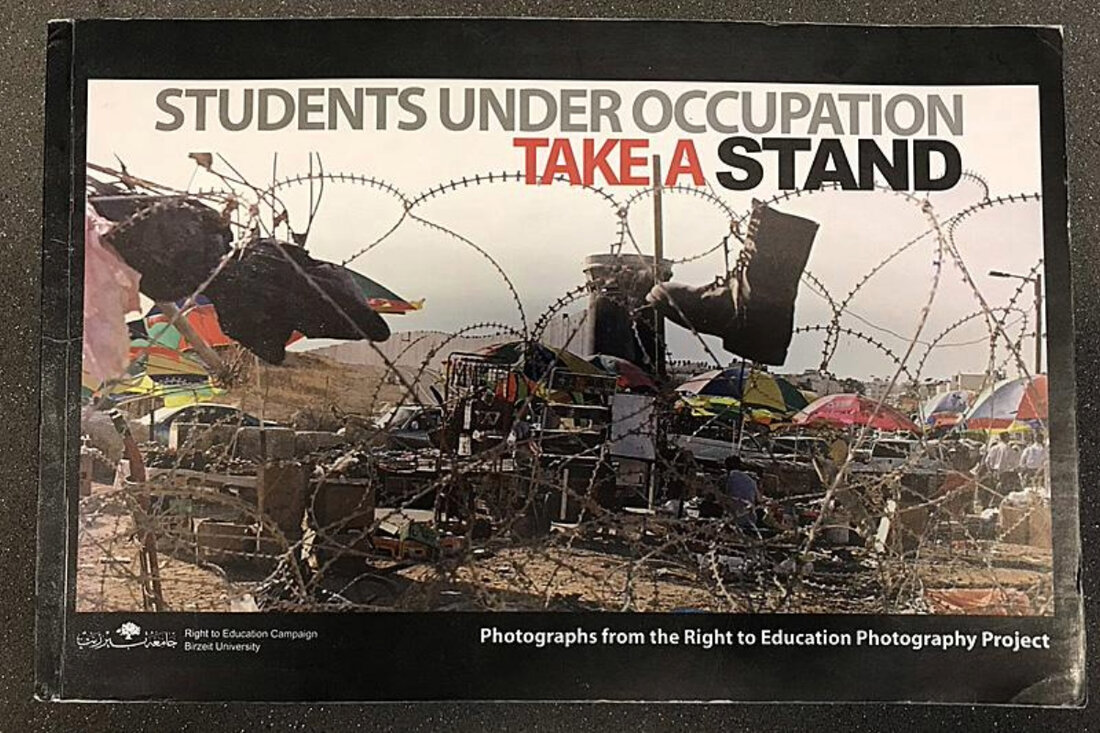

This desperate maneuver is not without precedent. Palestinian scholar Yamila Hussein teaches us that during the First Intifada (1987–1993), the occupation effectively outlawed Palestinian education. Schools and universities were shuttered, often without explanation, and students and teachers were harassed or even attacked for carrying books and other materials or participating in unsanctioned educational activities. However, as has so often been the case, this practice of outlawing Palestinian education created conditions for Palestinian people to create their own educational institutions beyond the gaze of the occupation and its soldiers. Thus, the occupation’s efforts to destroy Palestinian education in fact led to an epistemic rebirth among Palestinians in the occupied territories. For the first time since 1967, they had full control over who would teach their children, what they would be taught, and how.

What can we learn from the Palestinian response to the occupation’s full spectrum assault on education in the occupied territories? Hussein boils down the Palestinian response into three strategies that have become general principles within the Palestinian national liberation struggle.

Education is a right. Every person has the right to learn, to read and write, to comprehend the world on their own terms, and to use language and other skills to transform their reality in concert with others. Education is a weapon for liberation. Knowledge of every social system, law, technology, form of medicine, and means of meeting basic human needs is essential in order to resist occupation and oppression. Education is a venue for becoming part of the modern world. Of course, we must understand the difference between the current conditions faced by cultural workers and academics in Palestinian society and how the occupation’s assaults on journalism and academia isolated Palestinians from global civil society and the international press in the First Intifada.

We must understand “modern world” as a reference to global communications systems and political forums. To be able to participate in them as equals, education is necessary. This is not to say that Palestinians (or any oppressed people around the world) need Western or “modern education” to be worthy of recognition, but rather that they have the right to the tools necessary to advocate for themselves on the global stage in the present context.

How does this bear on our present moment in the West and in the United States? The lesson we ought to learn from the history of Palestinian education during the First Intifada is twofold:

We must consider how we can take responsibility for our own education and the development of these skills within our movements such that we will not live in fear of the state taking them away from us and thus be controlled by that fear. We must consider how we can best support the Palestinian national movement in its use of education as a resource with the resources and skills we have available.

Above all, we must remain steadfast and look for the opportunities of the present movement rather than fall victim to defeatism.