In 1954, the CIA backed a coup that deposed Jacobo Árbenz, the democratically elected leader of Guatemala. Árbenz became a CIA target after he began expropriating unused land — much of it owned by the U.S.-based corporation United Fruit Company — and distributing it to landless peasants.

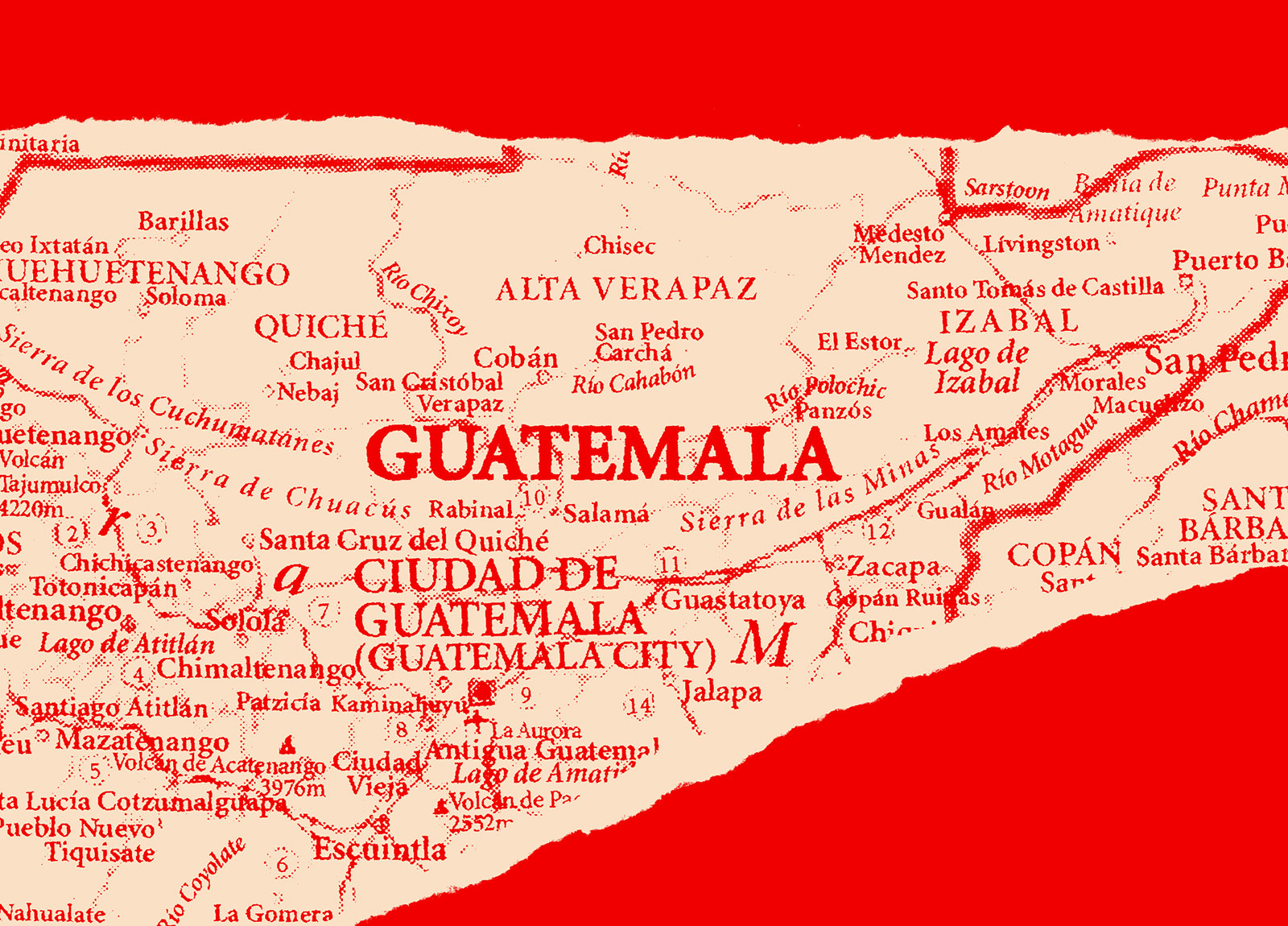

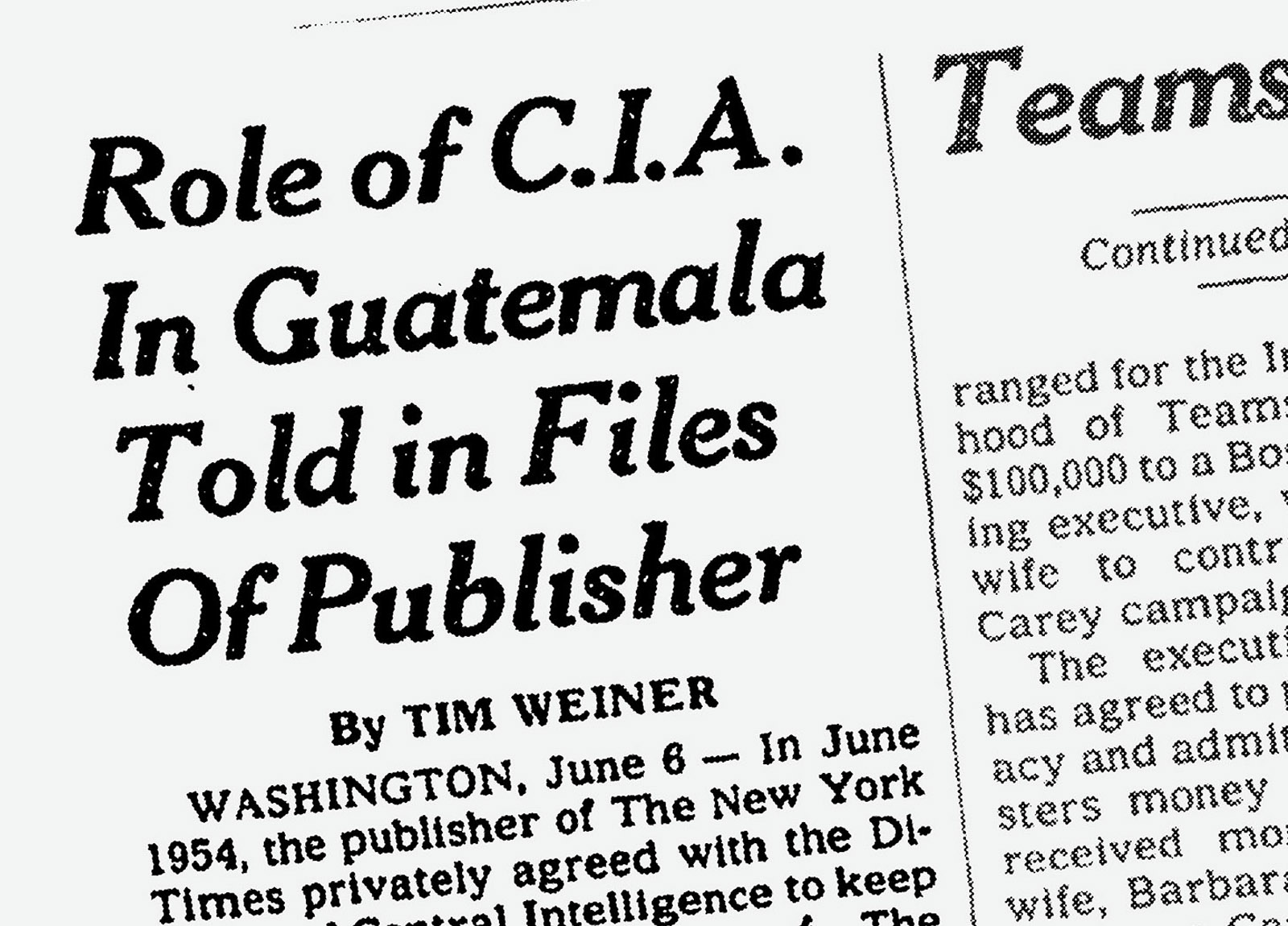

In this case, The New York Times’ involvement went beyond shoddy reporting. Days before the coup, in June 1954, Times publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger colluded with the CIA, as the paper itself later disclosed.

Sydney Gruson, The Times correspondent in Guatemala, was one of the few reliable international reporters on the ground in 1954. However, CIA Director Allen Dulles viewed Gruson as politically incompatible with American foreign policy, as the journalist had occasionally written favorably of Árbenz. Dulles personally contacted Sulzberger and requested that he remove Gruson from Guatemala.

''I telephoned Allen Dulles and told him that we would comply with their suggestion,” Sulzberger said in a memorandum. A little over two weeks after their conversation, the Guatemalan coup commenced. Árbenz was out of power before the end of the month.

As historian Piero Gleijeses and others have observed, Árbenz may well have been able to maintain his position had the CIA’s psychological warfare not swung momentum toward the U.S.-backed rebels. Would an honest journalist on the ground have made a difference?

“It certainly would not be unusual” for Dulles and Sulzberger to be so chummy, a former Times reporter and biographer of Dulles said when interviewed in 1997, on the occasion of the Gruson revelations. “This Gruson matter was not the only time.”

In more recent years, The Times has adhered to similar CIA and White House directives. In 2004, at the behest of the George W. Bush administration, the newspaper shelved a bombshell report on illegal spying by the National Security Agency until after Bush was reelected. In 2011, under pressure from the CIA, Times editors declined to publish reports that the agency had built a base in Saudi Arabia to launch drone strikes on Yemen.

Outside of their blatant meddling, The Times’ reporting cast Árbenz — a reform-minded politician, who had said in his inaugural address that he wanted to build Guatemala into a “modern capitalist state” — as a communist sympathizer. In The Times, Guatemala faced a “planned move away from democracy towards dictatorship” as the “red’s grip” on the country tightened. After Árbenz’s election, the editorial board wrote an oh-so-subtle editorial, titled “The Guatemalan Cancer,” which warned of the threat of “contagion” that Árbenz’ supposedly communist leanings posed to the region.

In contrast, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, the coup’s figurehead, was characterized as the beloved savior of Guatemala. In one post-coup front-page article, Castillo Armas “came back to the capital of his country a hero and received a thunderous welcome.” The vampiric United Fruit Company also received favorable coverage, as The Times wrote that it “pay[s] the highest wages” and “furnish[es] the steadiest employment” — if nationalized, however, “workers are likely not to be so well off.”

After the coup, The Times’ editorial board praised Castillo Armas for his plans to “rid the country of the communist menace” and wrote of the need to establish a government “based on the will of the people.” In the newspaper’s surreal calculus, Árbenz, Guatemala’s democratically elected leader, had less of a democratic mandate than a U.S.-backed military junta.

The Times willingly participated in the destruction of a nascent democracy, plunging Guatemala headfirst into forty years of U.S.-backed military dictatorships, right-wing death squads and civil war. Hundreds of thousands of indigenous Mayans, trade unionists, students and leftists would be murdered by the government in the ensuing “Silent Holocaust.”