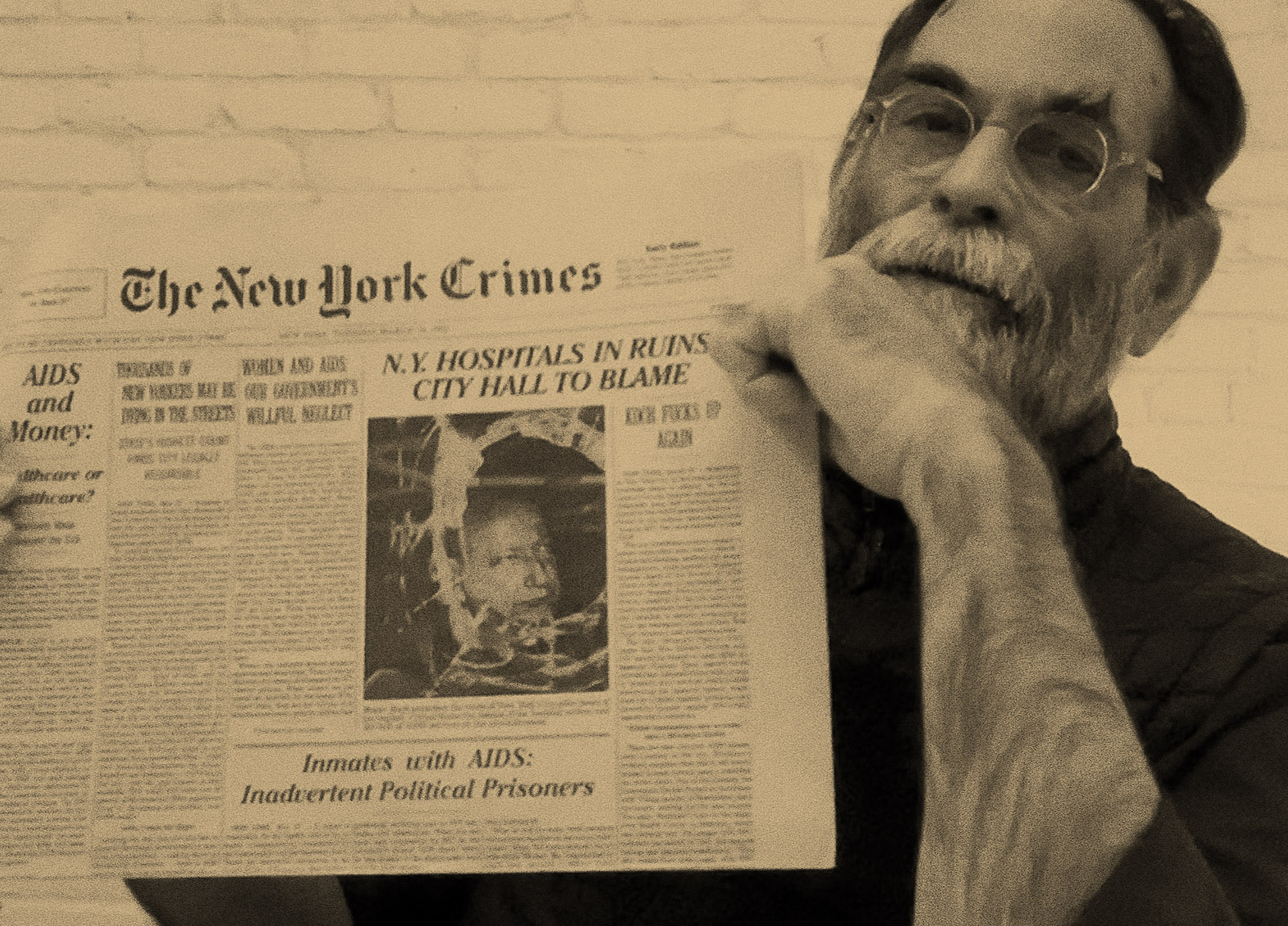

Avram Finkelstein is a long-time artist and activist. During the 1980s and 90s, he was a founding member of ACT UP and in 1988, as part of the Gran Fury collective, he co-produced the original edition of The New York Crimes, which covered what the newspaper of record was ignoring about the AIDS crisis. We sat down with him to discuss the legacies of New York City activism, the use of agitprop, and how to steal the voice of authority. This conversation has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

THE NEW YORK WAR CRIMES

Why don’t we start very concretely: Can you talk about the original New York Crimes? How did it come to be? What were you aiming for?

AVRAM FINKELSTEIN

As the paper of record, The New York Times has always been pernicious and suspect — always. But, as anyone who lives in New York can tell you, it’s kind of like the Bible. I don’t know why. It always has been. It’s a local newspaper, but The Times really has this idea of who they are in the world.

This project came about by accident, actually. I went to the Museum of Modern Art with my mother for a show of Fluxus artists, who were famous for, amongst other things, lists of ideas of performances and interventions. There was this list of interventions, and one of the many things was to make your own newspaper and hand it out on the corner. I saw that and I thought: Fuck, The New York Times has notoriously bad coverage of AIDS. This would have been 1987 or ’88. They were bad. And that's always been true. Since The New York Times reported on it, it must be true, even though none of it was true, as we remember.

NYWC

The Times has this overinflated sense of itself. And, despite all of the efforts to discredit the paper, it continues to retain that voice of authority. Do you have any explanation for why it continues to be so authoritative?

AF

Part of it is the broadness of what they cover — science, technology, politics, the arts, theater. The only thing they don't do is self-criticism. That’s part of how it functions — but that is capitalism. We’re describing capitalism, there. The false promise of abundance is what capitalism is. And The New York Times is a capitalist rag, there’s just no way out of it. And yet, it’s considered to be a “liberal” paper, even though it is so frequently wrong and politically pernicious.

NYWC

People don’t dismiss The Times in the way they do Fox News, because they're supposed to be liberal, authoritative, neutral. So they get a pass.

AF

The fundamental problem with The Times — whether with AIDS or with Israel and Palestine — is that it presents a narrative that is determined to serve power structures. Their narratives are invariably in service of power, not resistance to power.

What has happened in the Middle East for decades is the idea that it’s impossible to intervene. The structures of power are dependent on our thinking of this as an impossibility. And resistance is about understanding possibility in all of its permutations.

NYWC

What did resistance to The Times look like in the 1980s and ’90s?

AF

It was a matter of stealing access to the voice of authority. A peculiarity of The New York Times was that it had less of a local circulation in New York City than The Daily News did, but much more national readership and influence. The Daily News also wasn’t covering AIDS, but ACT UP did not go to war with The Daily News. We went to war with The New York Times.

NYWC

What did that mean? Did you organize subscriber boycotts? Writers boycotts?

AF

No, no, we blocked delivery trucks.

NYWC

And of course you made this newspaper of your own, the original New York Crimes.

AF

This newspaper was meant to cover the various issues that The Times was not covering. It was really bad; they didn’t do a thing. Each piece was written by a subcommittee and ACT UP: women and AIDS; AIDS and prisons; IV drug use; AIDs in the media . . .

NYWC

A big part of the New York Crimes project was also the actual distribution of the papers. Can you talk about that?

AF

The idea from Fluxus was to hand [copies of a paper] out on the street corner, but we did not hand them out. At the time, you could buy pretty much any newspaper — The New York Post, The Daily News, The New York Times — at kiosks on pretty much every corner. It was an honor system: You put in a quarter and you took out a paper. So, I thought: We could hand them out on the street corner, but wouldn’t it be better to just steal access?

So we researched when the delivery trucks came and removed yesterday’s papers and put the new papers into each kiosk throughout the city. And then we sent teams of people to cover the various neighborhoods, following the trucks with rolls of quarters. There were three people on each team: one as a lookout, one to pull all the newspapers out and take the front covers off, and then a third to put our covers around The Times and then put all the copies back in the kiosk. So people would go get their paper and wouldn’t know it was our version until they took it out of the kiosk and started looking at it.

NYWC

It sounds like ACT UP pursued a kind of two-pronged policy: both trying to change the way The Times covered AIDS and boycotting and protesting at the same time. Were there tensions within the group — people who were advocating one strategy over another?

AF

There was no tension whatsoever between multiple strategies. In fact, frequently, people would be involved in multiple approaches, because pressuring power structures to change involves both having meetings and issuing threats. Right?

NYWC

Did you get a response from The Times?

AF

We didn’t. The reason why we called it The New York Crimes was that we wanted to make it obvious that it was a satire. We even wrote “NOT TO BE CONFUSED WITH THE NEW YORK TIMES.” The reason for that was because CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador, had done a fake New York Times the year before this and had been sued by The Times. We didn’t want to get into a lawsuit. What we wanted was to steal access to the voice of authority; to their own idea of themselves as the voice of authority.

NYWC

What was that earlier version by CISPES like?

AF

Well, it was about El Salvador and a critique of the American government’s role in the Salvadoran civil war. They were similarly trying to steal the voice of authority from The Times. So I talked to them and they told me the whole story.

It was a fact-finding conversation, but it was great. My contact was this very famous model for Ralph Lauren who was a radical activist involved with CISPES and she taught me that, by soldering three nails together, you can create something that will puncture police tires, because no matter how you throw it into the street, it will always land with the point up.

NYWC

What was her name?

AF

Her name was Clotilde, but I didn’t think it was her real name. She was a very famous Ralph Lauren model.

NYWC

And she liked to puncture the tires of cars.

AF

She also taught me that, if there were mounted police, you throw ball bearings on the ground, and the horses will stop so they don’t hurt their feet.

It’s important to remember that, in ACT UP, there were many people who were happy to have meetings with the Centers for Disease Control or the National Institutes of Health — and there were also people who were puncturing tires. In the circles I traveled in, there were talks of political assassinations. It was a very fraught time. We all thought we were going to die. And it seemed like pretty much anything was fair game.