“I do not believe I am good. Or that we share a national legacy of innocence to protect and perpetuate,” the poet June Jordan wrote six weeks after 9/11. Of Americans, she said: “Who is more violent than we?”

Returning violence to its origins was a political and poetic gesture Jordan turned to often — particularly in an open letter she wrote on October 10, 1982. Jordan, in the letter, takes Rich to task for having signed a pro-Zionist statement that spring, and for being silent about the Sabra and Shatila massacre the previous month. She implicates every Zionist, every American in her screed. But her friends didn’t want to be implicated. As Marina Magloire writes in “Moving Towards Life,” an essay that traces the correspondence between June Jordan and Audre Lorde as well as the collapse of their friendship over the question of Palestine, a number of Black and Jewish poets, including Lorde, were “more interested in chastising Jordan for her tone and timing than in engaging with the content of her four-page critique.” Because of the reactionary interventions of people Jordan knew, respected, and even loved, the letter was never published.

Jordan’s literary career suffered from her lifelong commitments to anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism, and, most particularly, from her righteous and timely embrace of anti-Zionism. Already, by the time she was angry enough to write this letter, she had been blacklisted by the New York Times — to which she had been a frequent contributor — for writing poems about Palestine and Lebanon. The executive director of PEN America had chastised her for putting on a fundraiser for Palestinian and Lebanese children after Sabra and Shatila. Her New York City publisher had vowed to stop printing her books. So she knew what her speech could cost and spoke anyway, accepted the cost, chose it, felt it to be simply what she owed.

“Jordan recognizes that being part of an ethnonationalist state, whether born or chosen, carries the obligation to critique its violence,” writes Magloire in her essay. “The fact that a Black woman born in this nation can make this statement, with far more humility than Rich’s selective, cherry-picked identification with Israeli statehood, is a testament to the transformative possibilities of Jordan’s identity politics.”

This transformation beckons to us all in the letter’s stunning final turn. “I claim responsibility for the Israeli crimes against humanity,” Jordan writes, “because I am an American and American monies made these atrocities possible.”

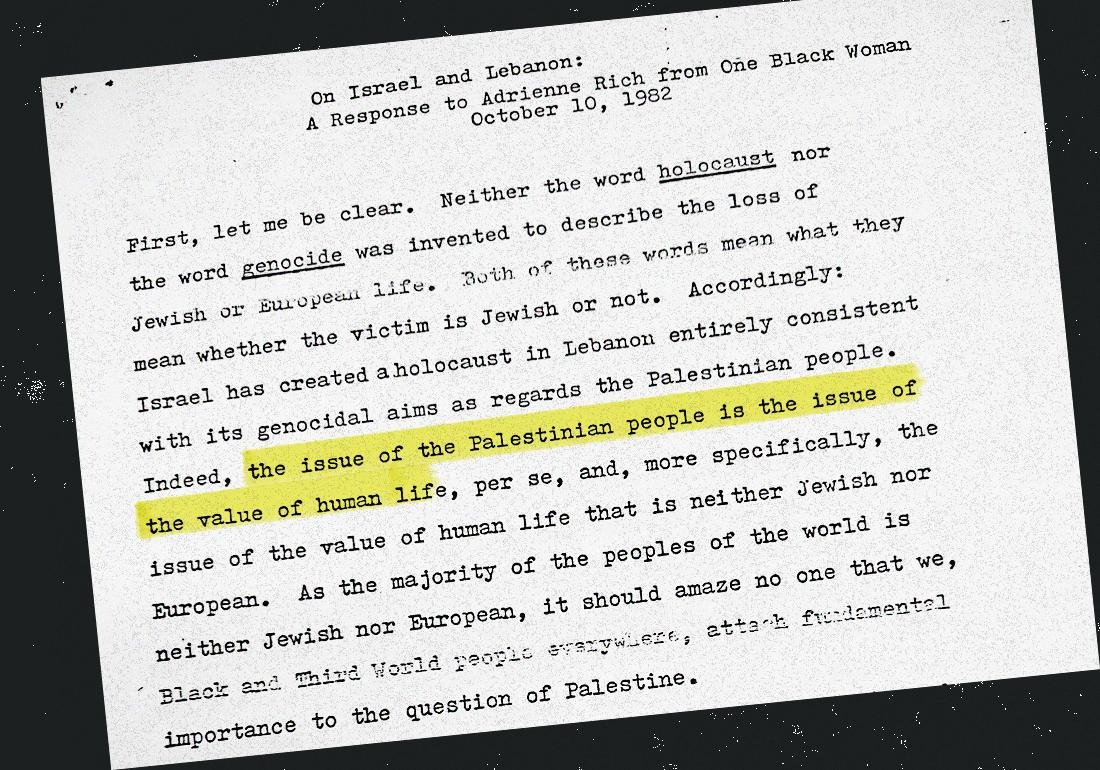

The full text of the letter, rescued from the archives of Audre Lorde, appears below.

June Jordan

October 10, 1982

First, let me be clear. Neither the word holocaust nor the word genocide was invented to describe the loss of Jewish or European life. Both of these words mean what they mean whether the victim is Jewish or not. Accordingly: Israel has created a holocaust in Lebanon entirely consistent with its genocidal aims as regards the Palestinian people. Indeed, the issue of the Palestinian people is the issue of the value of human life, per se, and, more specifically, the issue of the value of human life that is neither Jewish nor European. As the majority of the peoples of the world is neither Jewish nor European, it should amaze no one that we, Black and Third World people everywhere, attach fundamental importance to the question of Palestine.

When the 1982 invasion of Lebanon began I was stunned to learn that Off Our Backs carried a statement1 signed by Adrienne Rich on a subject even vaguely related to that developing holocaust. The Israeli slaughter of Lebanese and Palestinian men, women, and children, did not, after all, primarily raise issues of sexuality, or of 19th-century women writers.

I had not recently seen Adrienne affix her name to so much as a poem or a petition regarding the evils embodied by South Africa, El Salvador, Nicaragua, nuclear armaments, ten percent American unemployment, police violence in Black communities, and the resurrected compulsory military draft.

Surely, then, her emergence outside the most narrowly conceived white “feminist” realm must announce a very welcome, and urgent, broadening of her feminist grasp of this real and scarified and unequal world. But did she, in fact, condemn that Israeli campaign of massacre? Did she, in fact, identify the obvious nature of the Zionist state and its anti-Palestinian goals? Did she in fact, mourn for the non-European victims of her money, and my money, and our American monies (7.2 million dollars a day) poured into Israel--a state smaller than the state of Connecticut? Did she, in fact, scream aloud for her people--the people she dares claim as her own--to stop the cluster bombs and the phosphorous burning of children and the mutilation of women and then devastation of homes and schools and hospitals, as the Israeli armed forces thrust themselves forward and forward and forward into the ravaging agony of their creation? Did she, in fact, join the Israeli Peace Now dissidents who, as early as June, 1982, bravely put their white bodies on the line against this massacre committed in their name? Did she, in fact, claim responsibility?

She did not.

Does she now, after Sabra and Shatilah, does she now claim responsibility? She does not.2 Does she now, after 400,000 Israelis plunged into the streets to demand a tribunal to investigate Israeli function in the massacre of the people of those miserable refugee camps, does she now join that outcry with her own? She does not.

Does she tell you why the Palestinian people live and die in refugee camps? Why they don’t “go home”?

Does she remind all of us of the Israeli standards established in the Israeli trial of Eichmann in Jerusalem, to wit: That you cannot say you did not know. That you cannot say you never pulled the trigger. That you cannot say you did not turn on the gas. That you cannot say that you were only one among so many?

She does not.

This is what she does and she does it after Sabra and after Shatilah: She repeats that she is a Zionist. She wonders why is there so much fuss about this because evil is not a new phenomenon in the world. She emphasizes that she will join no “protest activities” to stop the evil done in her name. Her name, she says, is Jewish. You are anti-Semitic, she says, if you criticize anything and anyone Jewish. What, she says, by the way, about anti-Semitism, she says. What about that?

I now respond: I claim responsibility for the Israeli crimes against humanity because I am an American and American monies made these atrocities possible. I claim responsibility for Sabra and Shatilah because, clearly, I have not done enough to halt heinous episodes of holocaust and genocide around the globe. I accept this responsibility and I work for the day when I may help to save any one other life, in fact.

I believe that you cannot claim a people and not assume responsibility for what that people do or don’t do. You cannot claim to be human and not assume responsibility for the value of all human life.

To Adrienne, I make this public reply: Your evident definition of feminism leaves you indistinguishable from the white men threatening the planet with extinction.

Where you raise the accusation of anti-Semitism I accuse you: I accuse you of being anti-Palestinian. More, I accuse you of being anti-life.

I refuse to assume responsibility for your actions and your inertia. I do not accept you as my people.

Notes

1

Off Our Backs, July, 1982

2

Woman News, October, 1982